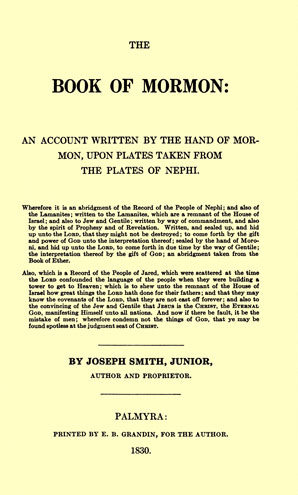

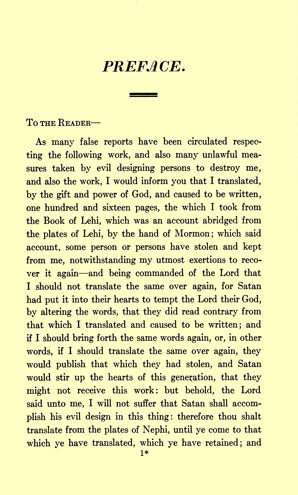

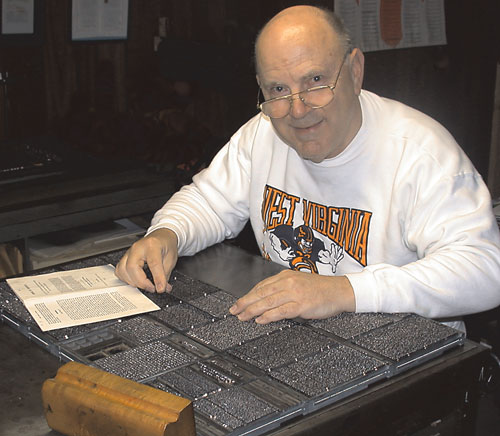

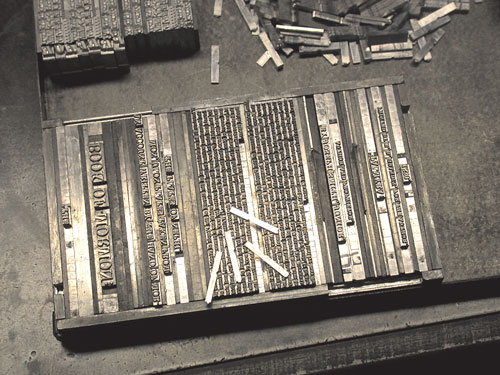

I had never been involved in the matter and I had never seen the original setting. But soon after the Conference, Louis Crandall sent to me Xerox copies of the original document with a plea for help in coming up with an accurate typographic facsimile. He emphasized that he would stand for nothing less than movable type! No photoengravings would be tolerated.

Several persons had studied the original previously, and had concluded that Lanston Monotype’s Scotch Roman would be a close match to the original font utilized. But this wasn’t working well because the “set” of the Lanston face was wider and thus, it was impossible to match the original document in a line-for-line fashion.

I did my own casting in Scotch Roman casting it on a narrower set body and reducing word spacing, but it still didn’t work well line-for-line. Also, the setting revealed to me that Scotch Roman was a very poor match to the original.